In the Hero’s Journey, that comforting narrative arc which underpins everything from mythology to the movies, the hero must always return to the (physical or psychological) place their journey first began.

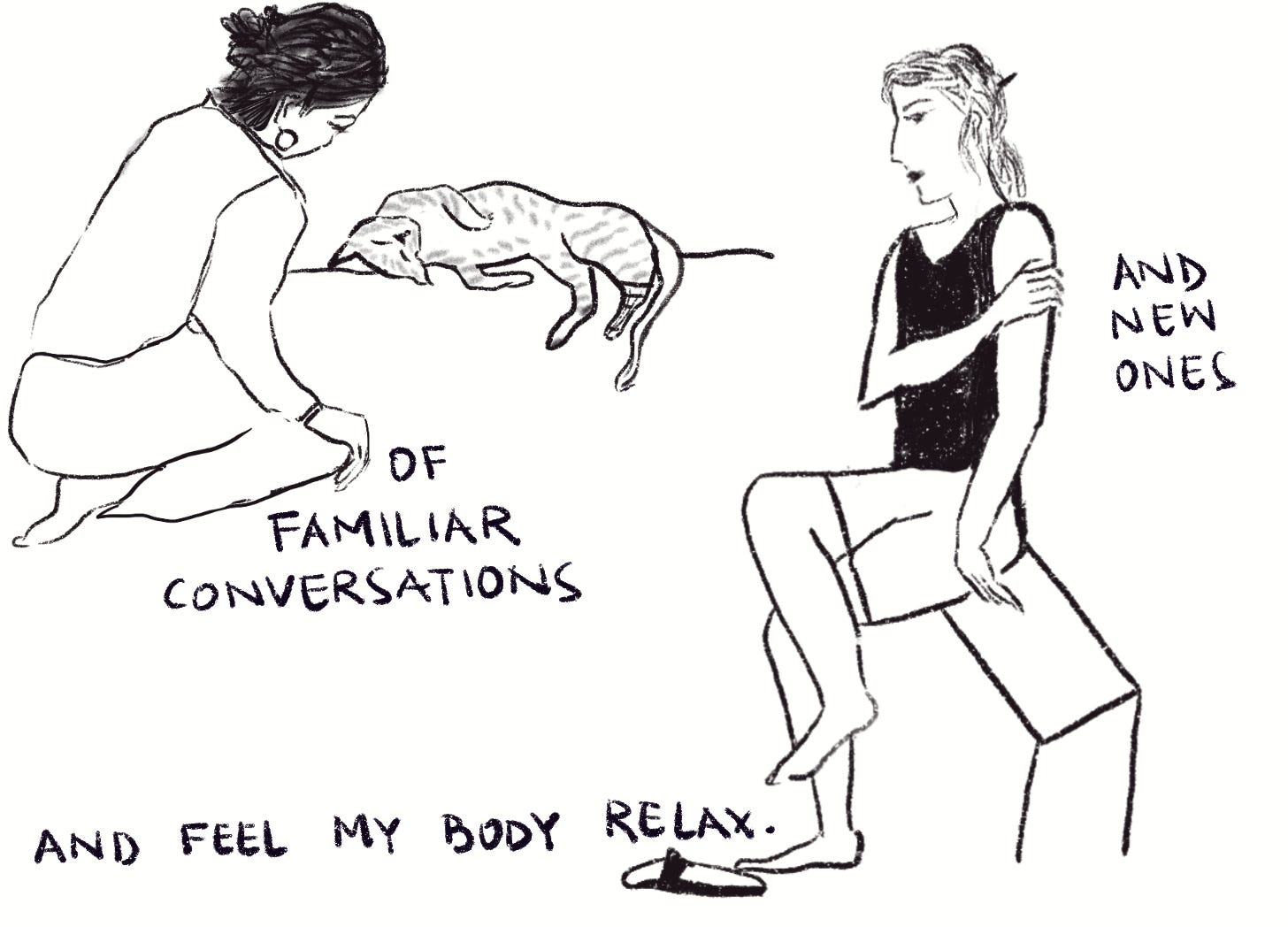

Everything the protagonist encounters on their travels — the trials, the omens, the victories and defeats — only begin to make sense in the context of home. It is amongst the familiar that we recognise what is new in ourselves.

Recent psychological research suggests that there is some benefit to seeing ourselves this way — as epic heroes and havers of main character energy. As protagonists, we are not merely shaped by fate and chance. We have agency, we shape our own narratives to see quests, allies, transformation and legacies instead of simply — the good and the bad.

Narrative identity, according to these psychologists, is at the core of how human beings understand the self. We tell others and ourselves a story by reconstructing the past, selectively perceiving the present and imagining a future that coheres with who we think we are, and what our purpose might be. The trouble with narrative identity, I have found, is that stories can feel like straitjackets. When we have an experience or a feeling that does not fit in with the story we tell about ourselves, it gnaws at us until we are forced to confront the horrifying possibility that maybe we are not a sum total of

Where we grew up

What we studied

What we do for work

Who our parents and loved ones think we are

Our political beliefs

And personal preferences

And physical bodies

Depending on what it is that jolts us out of the lull of the safe and familiar, narrative breaks can be profoundly traumatic or liberating or both.

In Buddhism, the Bodhisattva is a figure who appears before those who seek liberation, deploying whatever means are necessary at that moment to usher the seeker towards enlightenment. Bodhisattvas recur in Buddhist texts, referred to as Avalokiteshvara in Sanskrit, Chenrezig in Tibetan, Kuan-yin in Chinese, Kwanseum in Korean, and Kannon or Kanzeon in Japanese. They appear in both human and non-human forms, one of my favourites is the multi-functional bodhisattva, a shape-shifting dancer and magician:

”One of the most memorable of the numerous forms of the bodhisattva has a thousand arms and hands, many of the hands with implements such as flowers, vases of ambrosia, musical instruments, ropes, daggers, hatchets, and wish-fulfilling gems. Each of these tools may be useful in specific situations with different beings. In addition to multiple hands, some forms of the bodhisattva have eleven heads, to observe beings from different viewpoints and respond effectively with different guises.”

Last week, I encountered what I feel was a bodhisattva in the form of an owl, on a highway in New Delhi. She appeared on a moonlit night and offered me this perspective about storytelling:

"You can live your life as a snake (and there is nothing wrong with that).

You move through the earth experiencing each thing at the moment you encounter it, reacting to every danger, pleasure, vibration and provocation

as it appears.

Or you can live as an owl, with the knowledge that flight is always

a possibility, and no story can contain you. The sky will teach you that the world is bigger than you dreamt, you are smaller than you imagined

and there is more to your life than meets the eye.”

Wherever you are in your story this week, I send you ease.

I have only lived in Delhi a couple of years two decades ago, but I feel similarly about it--love it so much, but also feel on guard, ready to defend myself. I'm here right now for an extended stay for the first time after all these years, and I'm growing to love it again.

Also, your implication that the protagonist (me) has to go home made me shudder. But then I thought, I *am* home.

Thank you for sharing your beautiful drawing and writing.