Like many hopeful Indian parents, my mother enrolled me in extra-curricular classes, hoping they would stick. They did not.

My lack of enthusiasm for learning outside school should have become clear when it was discovered I had no aptitude for Math. A young man was paid to come over to our home and practise sums with me every Monday afternoon. Since the entire premise of tuition depended on my answering the door when my mother was away at work, I chose to hide behind our flowerpots and watch him ring and ring the doorbell until he left, defeated. I chose to fail Math instead.

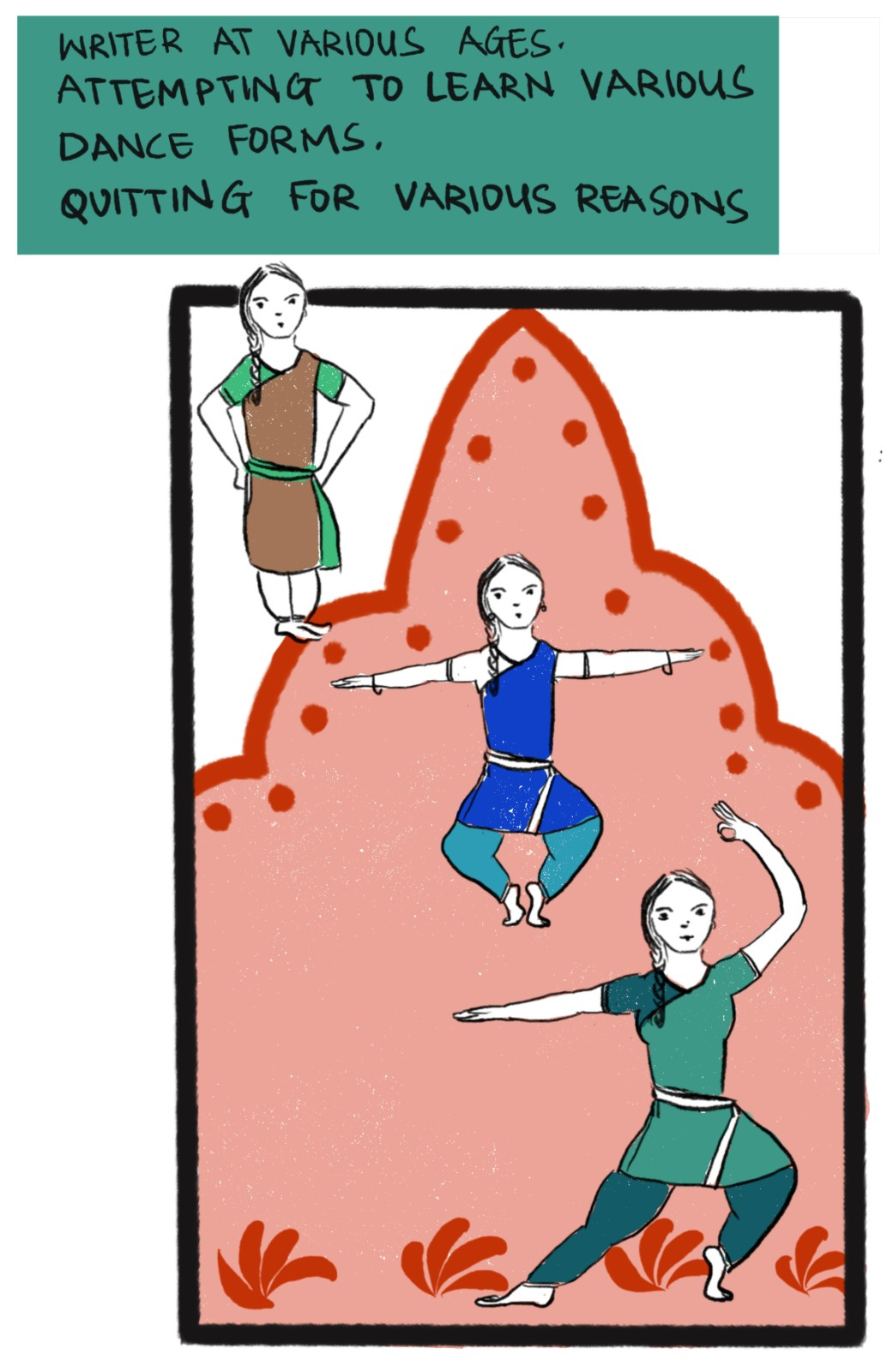

My mother didn’t give up. An aunt who was a famous classical dancer told her about the benefits of practise and discipline for young children, and I was sent off to learn odissi, bharatanatyam, contemporary dance. The aunt said she saw a promise of grace in my awkwardness, yet I hated and quit every form of dance I encountered. One teacher bored me, another scolded us too much. Shiamak Davar’s School of Contemporary Dance, where actual Bollywood choreographers taught hapless children, cool twenty-somethings and enthusiastic 40-year-olds (my mother) was too intimidating. My mother tried to enlist me in swimming classes and singing lessons next. I quit those too.

For a period, I was obsessed with theatre. But rehearsals were far away, long, intense and my mother was concerned about the lack of women in the theatre troupe. I quit again. By this time it became clear to us both that I couldn’t be forced into learning things. The one thing I remained interested in was the same thing my father and grandfather had lived off and suffered from: a love for writing.

I’ve quit a lot of things over the last two-ish decades: jobs, bosses, teachers, relationships, cities. Some of it has felt healing and good. All of it revisits me in sleepless moments of anxiety: am I just a quitter? how am I supposed to know when quitting is the right choice? What if I’m still the eleven-year old refusing to let my Math tutor in just because he was dull, choosing to spend the afternoon in blissful solitude instead?

The one that haunts me the most is a book I quit working on (at least for now, I tell myself each time this comes up) because it requires me to relive a whole lot of trauma. In 2013, I was shortlisted for a fellowship to work on a non-fiction book about India’s epidemic of sexual violence. In 2014, I was selected for the fellowship on the basis of a written proposal and a pretty intimidating interview with a panel of people I admired. Somewhere in between these two things, I found myself at the centre of a very public sexual assault trial that lasted for the next eight years. At first, reporting on and writing about the very things I was living through in court felt urgent and important. But to nobody’s surprise — a deep understanding of how screwed up this world and specifically the Indian legal system is, did not inspire or rejuvenate me. In fact, it shut my body down until it began speaking in the only way bodies know to signal distress — pain, depression, anxiety, hormone imbalances, disturbed sleep, an aversion to pleasure. I wrote approximately 50,000 words, sent my manuscript off, met a lot of doctors and therapists and realised I needed to quit the book (temporarily, at least) until I recovered.

The body also carries the cure. In recent years, developing an actual relationship with my body through various forms of movement has meant that I am able to revisit the altered reality of this traumatic period through the useful metaphor of physical injury. “If you live on this earth long enough, if you have a body, if you walk, move, dance or play, you will get injured, it is inevitable,” my capoeira teacher Mestre Poncianinho once told us in class. “That doesn’t mean you quit. You just change the way you train for some time.”

It is a comforting thought: physical and emotional injuries as the occupational hazard of being alive. The possibility that you can always train differently. It’s helped me reframe my childhood guilt over quitting things.

I have taken so many classes as an adult that I now definitively understand I was never the problem (apologies to my loving ma and the various teachers who were never let into my house, and those whose classes I quit). I thrive in learning environments where I’m empowered to experiment, fail and make mistakes. All my life, I’ve despised inflexible and rigid figures of authority. Boring people who thrive on subjecting captive audiences to monologues sap the life out of me.

It’s also helped me see the assault I suffered in my first job and the burnout from my last one as different kinds of workplace injuries. These injuries damaged my personal, professional, productive and social muscles. Training differently helped me find new ways to keep moving.

I worry I tell you too much about bodies, trauma, healing and recovering through joy but I also want to sing this from the mountaintop: regardless of whether people experience these specifically horrible things that I did, or have their own to choose from — workplace injuries, burnout, and the necessity of working under capitalism takes its toll on the body. The body also carries the cure. If you learn to listen, you’ll know when its time to change the way you train.

I write this newsletter with love (and occasionally, some existential dread). If you’d like to show your support or appreciation, leave me a tip!

Things I loved this week that I bring you as offerings:

1. Rega Jha is trying to quit smoking: “The past self is as fascinating a creature to me, now, as I, the non-smoker self, would likely be to her. For so many years, she couldn’t get through a single morning, let alone a day or week, without a smoke-break. She couldn’t sleep without the buzz, the slowdown. Life shaped itself around the craving. Airports were scoped for smoking rooms, bars for outdoor seating, house parties for balconies. Friendships and relationships deepened with other smokers by default because they made the same beelines, had the same priorities and restless hands. How impossible it felt then to ever quit, how genuinely unimaginable. How many times I even announced through hazy rooms to equally addicted friends: it’s fine not to live long but how could we live without this? Fast forward some years and there it is, the living without it. Until a verandah, an ashtray, and a reminder: all your selves are still in you, aren’t they?’”

Zoè Delautre Corral, a comic book artist whose work I love had this to say about memoir making, which really resonated with me:

“I think one of the biggest difficulties that I experienced when writing the script for this project, was that this story didn’t feel like it was only mine. I felt a lot of responsibility towards the people that took part in this story, and I had to consider to what extent I had a right to tell something that is as intimate to them as it is to me. But something that I feel liberated me and encouraged me to take the project forward was that I wanted to be free from guilt and shame. There’s a lot in this story to me about feeling guilty, and I got angry about carrying that feeling. I just told myself, if through freeing myself from this sadness I can alleviate someone else’s then it’ll be worth it. And everyone else that might be upset with me will hopefully forgive me eventually.”A beloved reader sent me this delightful poem on the subject of relentless productivity:

“If you put your nose to the grind stone enoughAnd keep it there long enough

In time you’ll say

There’s no such thing

Like brooks that babble

And birds that sing

These 3 things will your world compose

You, the grindstone and your goddamed nose”

More soon,Nish