Deep breaths and small steps

Despite all the extolled virtues of having a beginner’s mind, actually beginning new things is scary.

At some point in the past few years, I became obsessed with learning things.

It began with the usual suspects: yoga and dance classes, practising the simple, soothing phrases of a new language on an app. Like many pandemic-bakers, I learned how to make a starter and bake my own bread.

I burrowed ever-deeper into YouTube wormholes, learning how to cook various things from scratch. I bought and bookmarked books about the histories of dishes and dances from different cultures. New and healthy ways to cook from trendy doctor-chefs. Kitchen gardening, composting. Knitting (abandoned that), drawing (decided I never want to stop). In what felt like the most irresponsible and joyous decision I’ve taken as an adult, I decided to take time off journalism and go back to school to learn graphic design.

It’s been a few years and I’m still doing all the things I learned, learning more things related to those things, attending classes, taking notes, spending time, money and effort on a single pursuit: experiencing unfamiliarity, failure

and wonder.

I did not decide to learn again because I missed being a student.

The years I spent in school and college were marked with terrible social anxiety, a paralysing fear of failure and running up against inflexible

authority figures.

In my twenties, when I expressed a casual interest in gaining new skills (maybe I’d make a great coder? A contortionist? A forager?) I had no real intention of following through by actually attending a class or finding a teacher. Like the oft-memed wish to run away and live in a forest, my fleeting desires to learn new skills were just code for:

I like my life the way it is, but it’s pleasant to fantasise about another self

and what she might be capable of, if she were allowed to run free.

or

I don’t love the way my life is right now, but I feel better when I imagine

a future self who is free of these responsibilities and burdens.

What changed? For one, the science. Until the latter half of this century,

the vast majority of neuroscience was based on “the harsh decree” of neuroscientist Santiago Ramon y Cajal — that the brain develops only in childhood, after which it enters a period of neural decline. Neuroplasticity,

or the idea that adult brains can continue to learn and grow with a change

in stimuli, is a relatively new concept.

“In 1995, neuropsychologist Thomas Elbert published his work on string players that showed the ‘maps’ in their brain that represented each finger of the left hand – which they used for fingering – were enlarged compared to those of non-musicians (and compared to their own right hands, not involved in fingering). This demonstrated their brains had rewired themselves as a result of their many, many, many hours of practice.Three years later, a Swedish-American team, led by Peter Eriksson of Sahlgrenska University Hospital, published a study in Nature that showed, for the very first time, that neurogenesis – the creation of new brain cells – was possible in adults. In 2006, a team led by Eleanor Maguire at the Institute of Neurology at University College London found that the city’s taxi drivers have more grey matter in one hippocampal area than bus drivers, due to their incredible spatial knowledge of London’s maze of streets.”

For humans like me who are obsessed with the mythology of self-transformation (eg., turning lemons into lemonade, hero’s quests, movie makeovers, magical metamorphosis, shapeshifting shamans, the donning

of ritual costumes, alchemy), learning offers a real world way to re-train the brain we were born with, or a brain that was shaped by toxic and unsafe environments, into a brain that is able to adapt, heal and build resilience.

I realised my own brain was craving change before I learned any of this

about the human brain’s neuroplasticity. Like many writers, writing and speech were my primary methods of creative expression as a child. It was about the only thing I consistently received praise for, and so it became the thing I wanted to do most of all. As a journalist, writing also became my means of earning money. As is often the way — what I did became who I was.

Journalistic writing involves creativity but it is not a form of creative expression. A reporter is fundamentally an observer, a witness to someone else’s story (and most often their pain). I was witnessing so many things that felt so impossible to hold, that I could not find it in me to write for my own pleasure, sadness, love or for anything apart from a deadline. Despite this, journalism still felt safe and familiar; a place where I could substitute feeling things for making other people care.

The problem is, I was still feeling all the things. The more I witnessed,

the more I felt like I was turning into a physical embodiment of Edvard Munch’s most famous painting, Skrik (The Scream). I was raised by a single, working mother who had no time for recreational interests or hobbies.

Like ma, I had nowhere to put any of my feelings, no outlet for creative expression, and no concept of recreational learning.

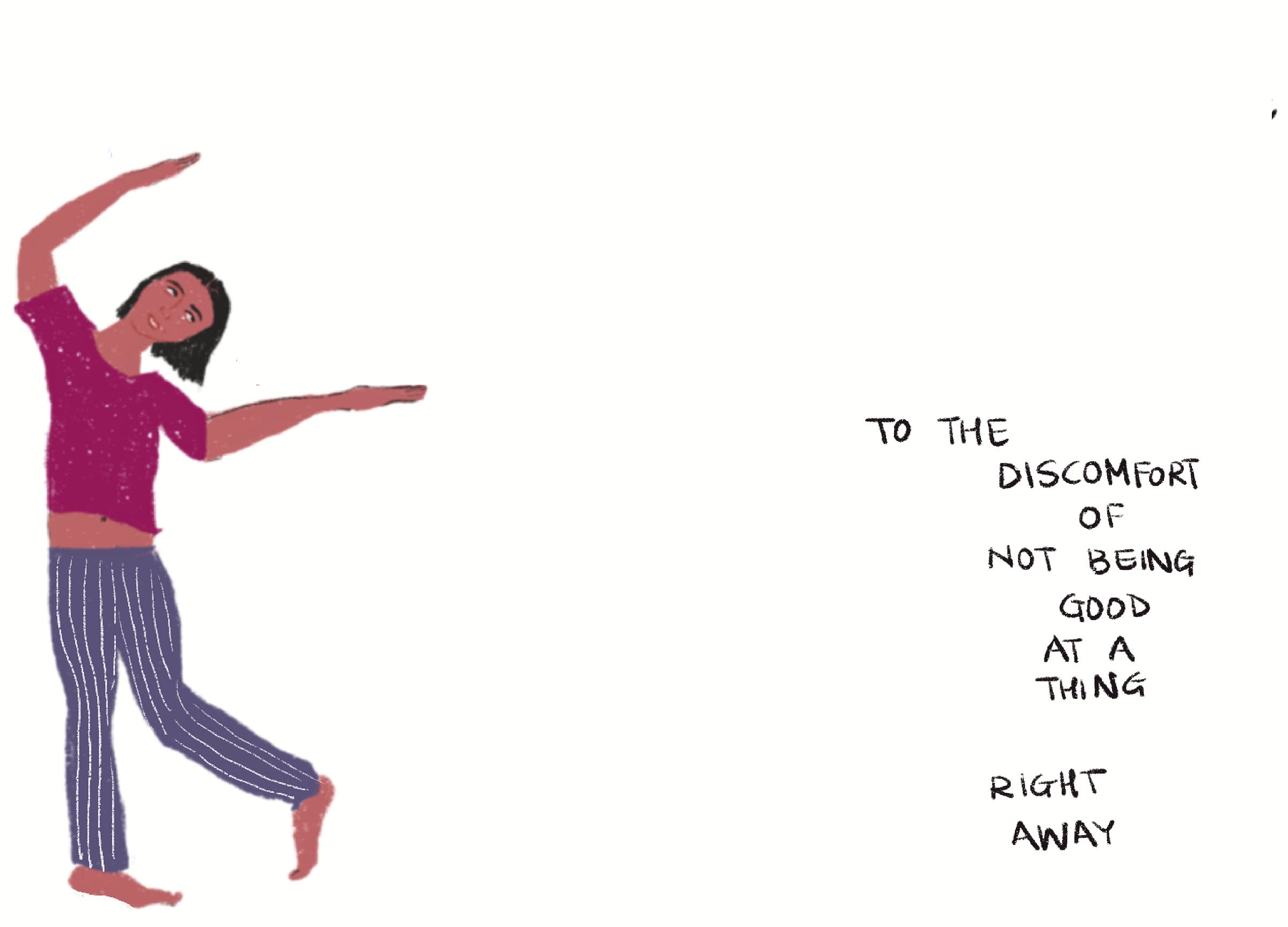

The problem is that despite all the extolled virtues of having a beginner’s mind, actually beginning new things is scary. When I first began to attend dance classes on an impulse, I felt things I avoided feeling at all costs as

a hyper-competent professional adult: inadequacy, insecurity and clumsiness.

I experienced every failure as a character flaw. Nothing in my life had actually prepared me for movement training (dancing at weddings does not count), and yet I felt tragically wrong, comically lost, woefully stupid and untalented. Why did I keep showing up for classes? How did I bear the humiliation?

For one, I felt no humiliation in my classes. Everyone made mistakes

and everyone was cool with it. Mistakes could be fixed, but for that, you

had to keep showing up.

Then there’s the other thing — I found wonder. Watching my teachers

dance with spontaneous and joyful abandon, or practise a sequence one million times until they get it right is inspiring and it fills me with hope.

I may never become a professional dancer, but I am able to stay on rhythm, improvise with melody and express myself through different styles — it’s a lot more than I could do four years ago. By showing up to learn something new,

I learned to focus on my effort instead of fixating on my lack of expertise. This is the wholesome, earnest, and slightly lovestruck feeling of being

a beginner — one that I could never access as a detached observer or

an expert.

The discipline part of things doesn’t get easier. My brain still begins to

make excuses on days when I know I have a physically or mentally challenging class lined up. I develop phantom aches, wonder if I’m pushing myself too hard, call my mother for advice. Nine times out of ten, I show up

in class out of sheer habit, with my heart pounding. But learning as an adult

is slowly rewiring my brain to forget what I learned in school. Failure is not catastrophic. It’s okay to be bad at things, its actually essential. It’s great

to have a place where you can be clumsy and make mistakes and go slow. How else will you learn?

Some things that lit up my brain this week:

1. This fascinating piece about what happens when we praise a child’s intelligence over effort, and the power (and peril) of being a “praise junkie”.

"Dweck discovered that those who think that innate intelligence is the key to success begin to discount the importance of effort. I am smart, the kids’ reasoning goes; I don’t need to put out effort. Expending effort becomes stigmatized—it’s public proof that you can’t cut it on your natural gifts.

Dweck also found this effect of praise on performance held true for students of every socioeconomic class. It hit both boys and girls—the very brightest girls especially (they collapsed the most following failure)”

2. How I Re-Wired My Brain in Six Weeks — Don’t let the clickbait headline turn you off this delightfully cheery BBC doc on neuroplasticity. Science journalist Melissa Hogenboom changes the shape of her brain by going running, meditating and learning to play an instrument for six weeks.

3. The surreal and beautiful art of Santiago Ramon y Cajal:

Nobel laureate and neuroscience baddie Cajal was also an incredible artist who made surrealist images of the human brain. Towards the end of his life, he turned away from human science and chose to study ants.

Loved reading this! Can completely relate to the constant and paralysing fear of failure. Time to retrain that monkey brain of mine. ;) Thanks so much for sharing!